This week for Take a Test Tuesday I took the revised Systemising Quotient (SQ-R) test.

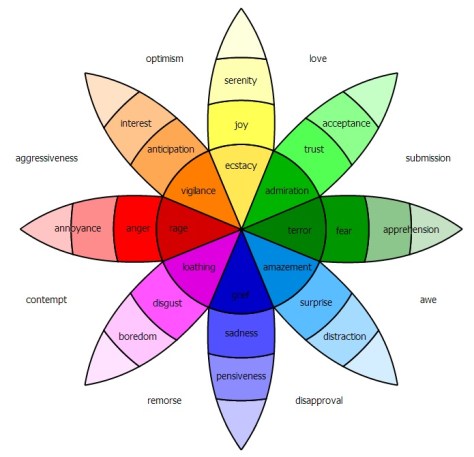

Systemizing refers to the drive to understand, construct, predict and/or control the rules of a system. Simon Baron-Cohen, in his desire to wedge autistics into his extreme male brain theory, contrasts systemizing with empathizing as the two primary ways in which humans make sense of their worlds.

The basic premise of the extreme male brain theory is that neurotypical males are better at systemizing and neurotypical females are better at empathizing. Hence, brains can be classified as either male or female according to these aptitudes. Autistic males and females are both better at systemizing, therefore, autistic people have “male brains” and autism is a condition of extreme male neurology.

Using that logic you could also make the case that female basketball players have “male bodies” (i.e. male bodies are on average taller than female bodies, female basketball players have taller bodies on average than females in general, therefore, female basketball players have “male bodies”).

Setting aside the extreme male brain theory, what can we learn from the SQ? The SQ is the subject of several research papers and each time the data show people with ASD generally scoring lower on the EQ and higher on the SQ.

The SQ attempts to measure systemizing in daily life, asking questions about how organized you are when it comes to your financial records, collections or favorite books/music. While the creators tried to avoid introducing bias in terms of subject matter, the test is still vulnerable to this. For example, I want to know the specs of new computer because that’s a topic I’m fairly familiar with.

I’m less interested in the specs of my car’s engine because that’s a subject I know (and care) little about. The same goes for knowing the species of animals and trees or the make-up of committees and governments. Those aren’t subjects I find highly interesting so regardless of how much of a systemizer I am, I’m only going to have a passing curiosity about them

Much of this still relies on personal interests, though perhaps it balances out in the end. The questions about how I bag my groceries and what my closet looks like made me laugh. I bag groceries by type because that makes them easier to put away at home. I hang my clothes in the closet by type so I can find what I’m looking for quickly.

My theory about systemizing? It all comes down to the fact that when you’re autistic, systemizing isn’t simply a preferred way of thinking, it’s a survival mechanism. Without systems and routines, we’d be constantly getting lost in the details.

One final note before we take the test. A lot has been written about gender bias in the EQ and SQ. It struck me as very telling that when the SQ was revised to remove some of the questions that were in “traditionally male domains” and add more questions that might be relevant to females, they removed questions related to investing, religion and culture and added questions related to shopping, cleaning, music and clothing.

Taking the Test

You can take the SQ-R (2005 revised version of the SQ) at the Aspie Tests site. Click on The Systemising Quotient (SQ) link and follow the prompts to get to the test page. I’m assuming you know the drill by now. There are 75 questions and you’re required to choose among strongly agree, slightly agree, slightly disagree and strongly disagree. Positive “strongly” answers score two points and “slightly” answers score one point. Possible scores range from 0 to 150.

It took me a little over 10 minutes to complete.

Scoring the Test

I scored an 85. Not surprising. I’m super organized, have a good memory for details and am insatiably curious about how things work.

I don’t think the SQ is binary in the way that EQ is. For example, on the EQ a positive answer to “I get emotionally involved with a friend’s problems” suggests empathizing. A negative answer suggests remaining detached or perhaps taking a logical problem-solving approach to the friend’s problems. This could be roughly construed as systemizing if we continue to look at it in a strictly binary way.

On the SQ, a negative answer to “I do not follow any particular system when I’m cleaning at home” suggests that one prefers using a system for housecleaning. But what does the opposite answer suggest? Certainly not anything to do with empathizing.

However, the EQ-SQ model sets the two tests up as “complementary” and goes so far as to demonstrate that a composite of EQ-SQ scores is steady across all groups (i.e. my EQ+SQ will be relatively equal to yours and everyone else’s, across all neurotypes). That suggests a strong negative correlation between the two tests.

When you look at the relationship between the AQ, EQ and SQ, it becomes evident that both the EQ and SQ act as a sort of proxy for AQ scores. In other words, they aren’t tests of empathizing and systemizing so much as they’re tests of the traits of autism. Of course autistic people will score higher than average on a test that asks a lot of questions closely related to core autistic traits and lower than average on a test that asks a lot of questions about social skills.

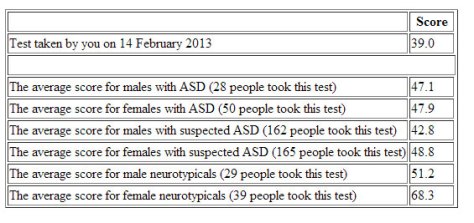

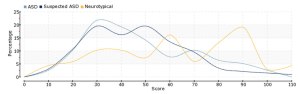

For reference, here are the mean scores from the 2005 SQ-R study:

ASD Male 77.8

ASD Female 76.4

ASD Total 77.2

Typical Male 61.2

Typical Female 51.7

Typical Total 55.6

(I prefer looking at the means from the original studies because the means provided by the Aspie Test site are based on self-reported neurological status, which may not be accurate.)

The Bottom Line

The SQ is an interesting measure of how dependent an individual is on routine, systems and categorization, but the use of the SQ as “proof” of the extreme male brain theory is highly suspect.