Last weekend, I had a meltdown and the next morning I tried to capture some scattered impressions of it to share. I’ve purposely left this raw and unedited, the way it unspooled in my head, to give you a feel for how chaotic a meltdown can be. While meltdowns are different for everyone, this is how I experience them.

——————————————-

A meltdown can go one of two ways: explosion | implosion.

Explosion

Everything flies outward. Words. Fists. Objects.

Implosion

Have you ever seen a building implode? The charges go off somewhere deep inside and for a moment you swear nothing is going to happen and then seconds later–rubble and dust and a big gaping hole in the ground.

——————————————-

It feels like a rubber band pulled to the snapping point.

——————————————-

What I don’t want to hear:

- It’s okay.

- (It’s not.)

- You need to pull yourself together.

- (I will, when I’m ready.)

- Everything will be fine.

- (I know.)

——————————————-

I’m not looking at you because I don’t want to see you seeing me this way.

——————————————-

It feels like the end of the world. It feels like nothing will ever be right again.

——————————————-

What I need:

- Space

- Time

- Absence of judgment

——————————————-

The headbanging impulse is intermittent but strong. I stave it off as best I can because:

a) my brain is not an infinitely renewable resource

b) headbanging scares other people

——————————————-

Meltdowns are necessary. Cleansing. An emotional purge. A neurological reboot.

——————————————-

Please don’t ask me if I want to talk about it, because:

a) there’s nothing to talk about

b) I don’t have the resources necessary for talking

——————————————-

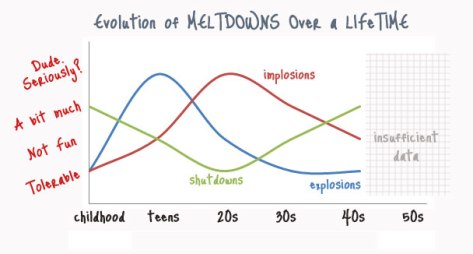

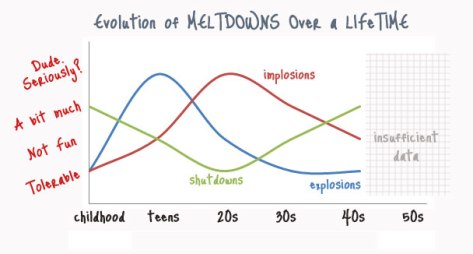

Evolution of meltdowns over a lifetime:

For my first 12 years, I internalize well. So well that I end up in doctor’s offices and emergency rooms with mysterious headaches, high fevers, stiff necks and stomach bugs. At various times I’m told that I don’t have meningitis, migraines, appendicitis. What I do have . . . that’s never conclusively decided. Things come and go, seemingly without rhyme or reason.

Puberty hits. Hormone surges make internalizing impossible. I slam doors, sob uncontrollably at the slightest provocation, storm out of the house, crank up my stereo. My anger becomes explosive. I pinball between implosions and explosions.

Early twenties, into my thirties, the explosions become rare but the implosions grow worse. I can’t get through an emotionally charged conversation with my husband–let alone a fight–without imploding. The headbanging impulse appears. Muteness takes center stage.

My forties–I can count the explosions on one hand. The implosions are down to a couple a year at most. As the meltdowns have lessened, the shutdowns have increased. This is lateral movement, not progress.

——————————————-

It feels like my whole body is thrumming, humming, singing, quivering. A rail just before the train arrives. A plucked string. A live wire throwing off electricity, charging the night air.

——————————————-

I’m 90% successful at staving off headbanging. The thing is: when that impulse arises, headbanging feels good. It’s . . . fulfilling?

——————————————-

- Will comforting me help?

- No.

- Do I want the meltdown to be over?

- Yes, but not prematurely.

- Would I like a hug?

- No.

- Am I in danger?

- No. I’m conscious of the boundary between stimming and serious self-harm.

- Do I want company?

- If you’re okay with sitting silently beside me.

- Can you do anything to make me feel better?

- Probably not. But you can avoid doing the things that will make it worse.

——————————————-

Muteness: Complex speech feels impossible. There is an intense pressure in my head, suppressing the initiation of speech, suppressing the formation of language.

——————————————-

My meltdowns aren’t so much about triggers as thresholds. There is a tipping point. A mental red zone. Once I cross into that zone, there’s no going back.

——————————————-

It feels like dropping a watermelon on the pavement on a hot summer day. The bobble, the slip, the momentary suspension of time just before the hard rind ruptures and spills its fruit, sad and messy, suddenly unpalatable. And no one knows whether to clean it up or just walk around it.

——————————————-

A shutdown is a meltdown that never reached threshold level. Either my threshold is rising or I’m becoming less sensitive to the precursors as I age.

——————————————-

Meltdowns are embarrassing. A total loss of control. Humiliating. They make me feel like a child. They are raw, unfiltered exposure.

——————————————-

Panic. Helplessness. Fear.

——————————————-

Imagine running as far as you can, as fast as you can. When you stop, that feeling–the utter relief, the exhaustion, the desperate need for air, the way you gulp it in, your whole body focused on expanding and contracting your lungs–that’s what crying feels like during a meltdown.

——————————————-

Please don’t touch me. Don’t try to pick me up, move me, or get me to change position. Whatever position I’ve ended up in is one that’s making me feel safe. If it makes you uncomfortable to see me curled up in a ball on the floor, you should move–remove yourself from the situation.

——————————————-

There is emotion at the starting line, but a meltdown is a physical phenomenon: The racing heart. The shivering. The uncontrollable sobs. The urge to curl up and disappear. The headbanging. The need to hide. The craving for deep pressure. The feeling of paralysis in my tongue and throat. The cold sweat.

——————————————-

The physical cascade needs to run its course. Interrupt and it’ll just start all over again a few minutes later. Patience, patience.

——————————————-

What I need when I’m winding down:

- deep pressure

- quiet

- understanding

- to pretend it never happened

——————————————-

The recovery period is unstable.

Exhaustion comes first. Mixed with anger, at myself mostly, for losing control.

My filters don’t come back online right away. Unless you can handle an unfiltered aspie, proceed with caution.

Finally, there is euphoria. A wide open feeling of lightness, of soaring, of calm.

——————————————-