The Aspie Quiz was recently updated to Final Version 3, which is a major update, so I thought it would be a good idea to retake it. Much of what’s changed is behind the scenes refinement of the test items and won’t be evident to the average test taker. If you’re new to the Aspie Quiz, you might want to read my original write up for more background. This post will focus primarily on what’s new.

If you’ve taken the Aspie Quiz before, you’ll likely notice that there are some new questions and that the wording of the test result has changed. Previously, test takers received Neurotypical and Aspie scores; currently the scores are presented as Neurotypical and Neurodiverse, with an outcome of “likely neurotypical”, “likely neurodiverse” or a mix of the two.

In the context of the test, the term neurodiverse includes autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dyspraxia (and perhaps OCD and Tourettes). However, the test still appears to be primarily a test for autistic traits. This is reflected in the statement that:

The goal of this test is to check for neurodiverse / neurotypical traits in adults. The neurodiversity classification can be used to give a reliable indication of autism spectrum traits prior to eventual diagnosis.

If you want to read more in detail about the development of the Aspie Quiz and what has changed over time, Leif Ekblad has published a paper detailing his research and a detailed history of the quiz. Of particular interest is the comparison of the AQ and Aspie Quiz scores, particularly for women. As many of us who’ve taken both have noticed, the AQ has a strong gender bias and the Aspie Quiz is more gender neutral. Anecdotally, the Aspie Quiz has always appeared to be a better predictor of whether someone is on the spectrum and that is addressed in the paper as well.

There are some aspects of the paper that I found problematic, but I’ll leave that to others to critique and focus here on the test itself. Before I do that, however, there is one sentence in the paper that jumped out at me that I want to share:

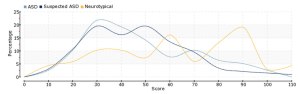

The idea that neurodiversity/autistic traits lie on the extreme end of a normal distribution is not supported by Aspie Quiz, rather the neurodiversity traits seem to have its own normal distribution overlapping the normal distribution of typical traits.

For those who have wondered why they receive two scores on this test, I think the above quote sums it up nicely. It’s also a good response to the oft-repeated fallacy that “everyone is on the spectrum” or “everyone is a little autistic.”

Taking the Test

To take the Aspie Quiz, start here. You have the choice to login/register or to proceed directly to the test. If you choose the former, you’ll be contributing to the test developer’s research regarding the stability of test scores over time (assuming you take the test more than once).

Once you’ve proceeded to the start of the test, you’ll first be asked some demographic questions. The information you share is used in the development of the test and has no impact on your scoring.

The test itself is 128 questions, answered on a Likert scale. The choices are: don’t know, no/never, a little, yes/often. The test will take about 20 minutes, so be sure you have enough time to finish it before starting.

Scoring the Test

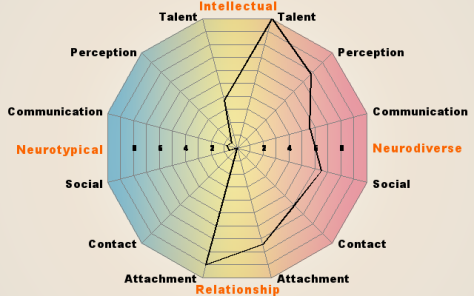

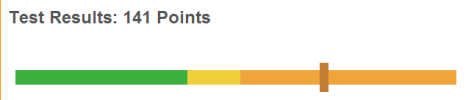

At the end of the test, you’ll get neurodiverse and neurotypical scores, along with a “likely” prediction. Here are mine:

- Your neurodiverse (Aspie) score: 156 of 200

- Your neurotypical (non-autistic) score: 54 of 200

- You are very likely neurodiverse (Aspie)

You’ll also get a nice spider web graphic and the option to download a PDF with more details, which I highly recommend doing. The PDF contains detailed information about which questions count toward which aspect of your score and includes some background information that may be helpful in interpreting your scores in each category.

On the previous version of the test, I scored:

- Your Aspie score: 170 of 200

- Your neurotypical (non-autistic) score: 32 of 200

- You are very likely an Aspie

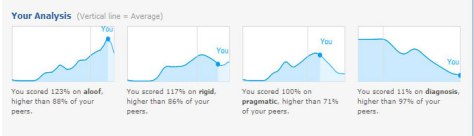

Since the last time I took the quiz, there are quite a few new questions and in particular a batch of new questions about sexuality and relationships. Given that I scored so high in Neurotypical attachment (i.e. sexuality) and relatively low in the social and contact on the neurodiverse side, I suspect the relationship and sexuality questions are the biggest factors in shifting my scores toward neurotypical.

Some of the questions in those areas were hard to answer accurately because they’re worded as if the test taker is seeking a romantic relationship or interested in dating, an assumption that doesn’t apply to either those in a monogamous relationship or those who are aromantic or asexual.

Although the quiz avoids gender bias, a few of the questions are biased in the direction of heterosexuality or presumption of asexuality as a non-neurotypical “preference”. More careful wording of some of the new relationship/sexuality questions to encompass both LGBTQ test takers and those in monogamous relationships would help mitigate some of this problem.

But I also think that the role of romantic and sexual preferences in the test outcome would benefit from a different approach. It’s stereotypical and ableist to assume that neurotypical people are sexual and neurodiverse people are not. The neurodiverse people that I know are distributed over a wide spectrum of sexuality and sexual preferences, from asexual to hypersexual and everything in between, just like the neurotypical people that I know.

Looking at the Attachment category questions in the PDF, all of the Neurotypical Attachment traits are related to sex. The Neurodiverse Attachment traits, on the other hand, are questionable in their relevance to attachment versus things like language pragmatics and learning social skills through rules. Surely neurotypical people are interested in aspects of attachment other than sex. More importantly, it’s disappointing to see a test of neurodiversity ascribing typical autistic social traits to “attachment disorder.”

Overall the new questions are much like those of the earlier version that I took: a mix of the highly relatable with the expected, plus a few that I have trouble tying back to any known autistic traits.

I was amused by “Do you have a need to confess?” because I’m so bad at lying or concealing things from people and inevitably feel the need to spill my guts at the drop of a hat. There were a few perplexing ones, including the one about walking behind people and the one about examining people’s hair. (And I still don’t get the slowly flowing water question – though I suspect it identifies people who are visual stimmers in general.) I wasn’t sure how to interpret the “afraid in safe situations” question. Maybe it’s meant to reveal phobias or irrational anxiety?

Finally, the “criticism, correction, direction” question is repeated twice with slightly different wording (possibly as a check question).

The Bottom Line

Of all the online tests I’ve evaluated, the Aspie Quiz has always felt like the most accurate in overall scoring and the most comprehensive in variety of questions and that’s still the case. I’ll be curious to see how re-takers feel about their scores and what direction, if any, scores have shifted in.