Through the magic of old home movies (actually DVD transfers of grainy super 8 footage), I’ve been able to study bits of my childhood, looking for typical early childhood signs of autism.

Hindsight is not only 20/20 it’s very entertaining. I decided to liveblog scenes from my autistic childhood, so you can share in the fun.

Let’s go back in time . . .

DVD #1: The Early Years

Through most of the first disc I look like an average baby and toddler. Maybe a little hard to engage at times. I’m often staring intently at something off camera. I’m interested in objects as much as people. Give me a baby doll and I’ll probably hug her. Or wield her like a club. It’s a toss up.

I’m not the most expressive baby. I more often look panicked or confused or grumpy than happy. Hmmm, when I do look happy it tends to be the shrieking, hand flapping sort of happiness.

Then this happens:

Doesn’t respond to his or her name or to the sound of a familiar voice.

Soon I see more clues:

51:55 – I’d rather sit and bounce on my ball than throw or kick it.

53:01 – The first of many shots of me happily swinging on my backyard swing set.

58:38 – A little hand flapping for the goats at the petting zoo.

1:04:14 – Here I am getting a haircut. I loved going to the hairdresser because it meant I got to play with the rollers and hair clips. And by play with, I mean sort by size and color.

Doesn’t play “pretend” games, engage in group games, imitate others, or use toys in creative ways.

DVD #2: Vacation!

Being away from home causes me to stim nearly nonstop. In the first twenty minutes, I’m 3 to 4 years old and still an only child. I wonder if being the first child–with no siblings to compare my behavior to–makes my autistic traits less obvious to my parents.

3:40 – Here I am rocking back and forth in my stroller at Santa’s Land.

5:21 – My parents prompt me to wave to the camera. Again. I rarely wave unless they tell me to.

Uses few or no gestures (e.g., does not wave goodbye)

8:12 – An entire reel of me sitting beside my inflatable pool, washing the grass off my feet. I’m still doing it when the camera shuts off. I seriously did not like having grass stuck to my feet. Or grass in my pool.

9:40 – Happily swinging on a porch swing.

9:52 – Really happily swinging on a chain link fence. Okay, more like happily full body slamming the chain link fence.

Flaps their hands, rocks their body, or spins in circles

10:39 – Staring intently at an animatronic display. So intently that I have my face pressed flat up against the glass.

11:40 – Swinging on a glider. A disproportionate amount of these movies are of me swinging on things.

Exhibits poor eye contact

12:42 – More rocking, this time while posing in front of a statue of a giant pig.

12:56 – More intense staring at animatronic gnomes.They’re rocking gnomes. I love them. In fact, I love them so much, I’m rocking in time with them.

13:20 – More staring. This time at dwarves.

14:18 – Here I am rubbing Humpty-Dumpty’s egg-shaped body. Over and over again, my parents pose me on or next to something and I immediately start rubbing my thumb or palm over the closest surface.

Engages in repetitive gestures or behaviors like touching objects

15:49 – Swinging from the rope of the school bell in an old fashioned schoolhouse.

16:32 – Bouncing up and down with the White Mountains in the background.

You get the idea. Ten more minutes of vacation footage and I’m constantly in motion. Bouncing, rocking, fidgeting with my windbreaker zipper, kicking my feet, flexing my knees, jiggling my feet, rubbing surfaces, hand flapping.

Moves constantly

I’m thinking it’s time to shut the DVD off, assuming I’ve made my point, when I see my sister do something I haven’t done once in more than 90 minutes of video: she points. She’s about a year old, and she’s pointing at the petting zoo animals. That’s when it hits me. I have one of the classic early childhood autism symptoms–a failure to point at objects.

Doesn’t point, wave goodbye or use other gestures to communicate

Soon we’re at Disney World with a family friend. She and my sister point again and again at things they’re excited about. I don’t point at anything. Not once.

30:06 – I’m about six here and I’ve learned to wave at the camera without being reminded. I’m riding on a carousel and wave at the camera every single time I go by. Yep, I’ve got the waving thing down good.

35:36 – We’re at Gettysburg. I’m around seven years old. My mother and sister are posing by a canon, waving at the camera, chatting away. I’m climbing on the canon, rubbing the canon, pretending to ride on the canon, paying no attention to them or the camera.

Appears disinterested or unaware of other people or what’s going on around them

It’s interesting to see footage of my sister and I at similar ages. I see how much more likely she was to engage with the camera, to wave spontaneously, to be smiling or talking or paying attention to the people around her.

I also see that I took a lot of cues from her. She’s four years younger, but at times–like when we’re interacting with characters at Disney World–I’m obviously watching her and following her lead.

And now that I’m no longer the sole focus of the camera’s attention, I’m a lot more likely to just wander out of the frame.

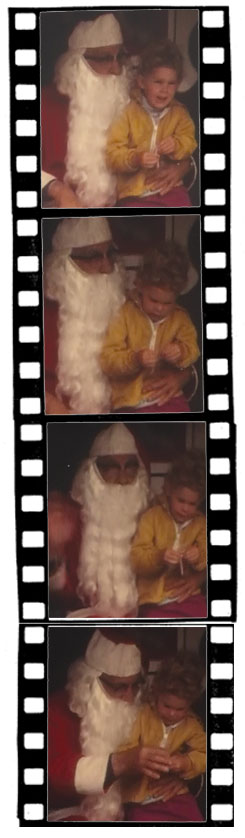

DVD #3: A Slew of Holidays with a Dash of Empathy on the Side

12:10 – Back in time again, to my 2nd birthday party. It’s a huge one. Every cousin, aunt, uncle and grandparent wedged into our basement rec room. I’m looking a little overwhelmed, circling a pole in the background as my cousins mug for the camera. When it’s time to blow out the candles I bravely poke a finger into the icing, lick it off my finger and immediately grab a napkin to clean my hand. Some things never change.

17:51 – Halloween. I’m six years old and for the first time I see evidence of my inability to tell if anyone is paying attention when I’m talking. As I scoop the seeds out of my pumpkin I’m rambling on about something to my sister who is too young to understand and my mother who is bustling around the kitchen, not even in the frame half the time. I’m blissfully undeterred.

Tends to carry on monologues on a favorite subject

20:12 – A bunch of Halloweens flash by. I’m Raggedy Ann. I’m a nurse. I’m a cat. Every costume has a stiff plastic mask which I pull off repeatedly. After yanking off the cat mask, I tug at my hair with both hands. Even today, my single most vivid memory of Halloween is the warm wet sensation of plastic against my face as my breath condensed on the inside of those masks.

29:50 – It’s snowed! My eighteen-month-old self is skeptical. I touch the snow with one mitten. Look at my hand. Immediately begin flapping. Cut to a shot of me a few months later, enjoying a fine spring day by toe-walking up the driveway. Yet another thing I’d say I never did if I hadn’t seen it here.

May be unusually sensitive to light, sound and/or touch

40:19 – My sister and I are playing with my dolls in my room. By playing I mean I’m lining them up against the wall by height while preventing her from touching them. She enjoys this about as much as you’d expect a toddler to.

Obsessively lines up or arranges things in a certain order.

Looking back at these old films through the lens of autism is really enlightening. I had telltale signs of Asperger’s syndrome at a time when AS didn’t exist. I don’t remember much of what I’ve related here, but I do remember being a generally happy kid in my preschool years. Because I didn’t attend nursery school or daycare, I guess spent my first five years in a bit of a bubble, happily stimming my way through Santa’s Land.

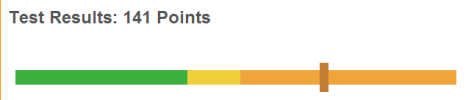

Signs of Autism in Early Childhood

While I’ve highlighted many of the early signs of autism in my observations of my younger self, each child is different. You can find comprehensive lists of early signs and symptoms at Mayo Clinic: Autism Symptoms and/or the CDC’s ASD Signs and Symptoms.