This week for Take-a-Test Tuesday, I took the Broad Autism Phenotype Questionnaire.The only online version I was able to locate is seriously flawed so I’m going to recommend against taking it. However, I’ve been looking for an excuse to talk about the Broad Autism Phenotype and here it is! If you’re the parent of an autistic child, I have a question for you about the BAP at the end.

The Broad Autism Phenotype (BAP) is a fancy way of saying that nonautistic relatives of autistic individuals often have subclinical autistic traits themselves. As far back as Leo Kanner’s original study on autism, researchers have been observing a tendency for parents of autistic children to exhibit traits that are milder but qualitatively similar to the defining characteristics of autism, especially in the area of social communication.

Consequently, the Broad Autism Phenotype Questionnaire (BAPQ) focuses primarily on social communication, rigid personality traits and pragmatic language deficits, which are thought to be the most common characteristics of BAP. It is designed to be taken by nonautistic individuals, specifically parents of autistic children.

The BAPQ has questions in three areas:

- social communication deficits (aloof personality subscale)

- stereotyped-repetitive behaviors (rigid personality subscale)

- social language deficits (pragmatic language subscale)

Each of these areas corresponds to one of the core domains of autism (though that will change with the DSM-V): social, stereotyped-repetitive, and communication deficits. The researchers who developed the BAPQ defined the three subscales that the test measures as follows:

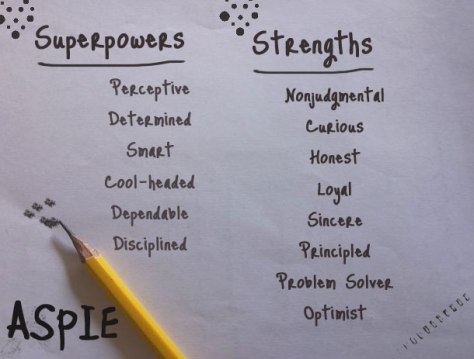

Aloof personality: a lack of interest in or enjoyment of social interaction

Rigid personality: little interest in change or difficulty adjusting to change

Pragmatic language problems: deficits in the social aspects of language, resulting in

difficulties communicating effectively or in holding a fluid, reciprocal conversation

In developing the BAPQ, traits like anxious/worrying,hypersensitive to criticism, and untactful (which can all be autistic traits) were omitted because the researchers believed they were observed less frequently as part of the BAP. An individual is considered to “have” BAP if they exceed the threshold score on two of the three subscales.

It’s interesting to note that parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles of autistic children also have higher than average rates of major depression and social phobia. A number of studies (like this one) have indicated no direct relationship between BAP and major depression or social phobia in autism families. There have also been a number of studies that have refuted the notion that raising an autistic child is the cause of these elevated rates (take a look at the discussion section of the linked to study if you’re curious about how they reached this conclusion and what other factors might be at work).

Taking the Test

The only place I could find to take this online is at OKCupid. The test is riddled with grammatical errors and the result summaries are downright insulting. The scoring also appears flawed, so unless you have literally nothing better to do, I don’t recommend taking it. Seriously, go see what’s new on Tumblr or something.

My primary purpose in analyzing the online test is to point out how flawed it is and how it doesn’t align with the intended scoring method of the original BAPQ. You might want to go through the test to see what questions are included but you can also find the questions on page 10-11 of this PDF.

Scoring the Test

It’s unclear how the online test is scored. The original BAPQ has 6 answer choices, scored on a scale from 1-6, but the online test collapses the first and last two choices. The BAPQ cutoff scores are averages (2.75 – 3.5), which were developed as part of a study using the 1 to 6 scale. The OK Cupid test appears to be using a summed score rather than an averaged score to determine a cutoff, so maybe the person who posted this decided to make up their own cutoff?

Like I said, you’d be better off wasting fifteen minutes on Tumblr.

At any rate, it provides four scores: diagnosis (overall score), aloof (aloof personality traits), rigid (rigid personality traits) and pragmatic (pragmatic language problems). The fact that the scores are presented as percentages (in excess of 100, no less!) makes no sense. Even worse is the little “diagnostic” description provided.

Mine says: “You scored 123 aloof, 117 rigid and 100 pragmatic. You scored above the cutoff on all three scales. Clearly, you are either autistic or on the broader autistic phenotype. You probably are not very social, and when you do interact with others, you come off as strange or rude without meaning to. You probably also like things to be familiar and predictable and don’t like changes, especially unexpected ones.”

I looked at all of the possible outcome descriptions (you can force the test to reveal them at the end even if they don’t pertain to your score) and they’re all just as meaningless. Some are downright wrong. Many of them state that you’re on the BAP if you are over the cutoff on one subscale but not the other two, which is incorrect.

Basically, the “results” of the online test are useless.

If you’re interested in taking the BAP and getting a valid score, you can look at the appendix of the original research paper which has the full set of questions with a scoring key.

The Bottom Line

The online version of the test is too flawed to provide meaningful results. The BAPQ as administered in a clinical setting is used to screen for BAP in parents of autistic children, but the goal of screening is unclear.

My question for any parents of autistic children who might want to answer: do you see aspects of yourself in the BAP questions? Do you think the BAP has any significance for you personally?