It’s Take-a-Test Tuesday and this week I’m taking The Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised (RAADS-R).

The Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised (RAADS-R) is a diagnostic instrument that is intended to be administered by a professional in a clinical setting. It was primarily designed to identify adults who often “escape diagnosis” due to a “subclinical” level or presentation of ASD.

The 80 questions on the RAADS-R cover four symptom categories:

- language (7 questions)

- social relatedness (39 questions)

- sensory-motor (20 questions)

- circumscribed interests (14 questions)

Its validity as a diagnostic instrument was assessed in a 2010 study in which the RAADS-R was administered to 779 people at 9 different clinics in the US, UK and Australia. This is an impressive undertaking; the variety of testing sites suggests that results of the study are highly generalizable (that they can be extended to the general population). However, like all of the other instrument validation studies I’ve seen, this one also has an imbalance in male-female ASD participants, with a greater proportion of males in the ASD groups.

Pros and Cons of the RAADS-R

Pros:

- Self-scoring

- Validated in a clinical setting by a multisite study with a large sample size

- Provides overall and subscale scores

- Includes questions to assess sensory-motor skills

- Takes autistic childhood traits into account, even if they are no longer present

Cons:

- Many questions phrased as always/only/never

- Complex answer choices may be confusing for some

- Questions skewed toward social relatedness

- Longer than most other tests

Taking the Test

There are a few places you can take the test online:

- I took it at aspietests.org because I like the way they present the scores at the end. However, you’ll need to create an account to take the test there. (I did so about 2 weeks ago and they haven’t spammed me at all, which is nice.)

- If you’d rather not create an account, you can find a no-personal-information-required version at Aspergian Women United.

- There is also a paper based version of the test available but it doesn’t include a scoring key.

Wherever you decide to take the test, the format is the same. It took me about 20 minutes, but I spent a lot of time thinking about some of the questions so you may finish more quickly. You’ll be presented with 80 questions and for each you have to select one of the following:

- True now and when I was young

- True only now

- True only when I was younger than 16

- Never true

This answer format, which is unique to the RAADS-R, allows for the fact that some adults on the spectrum had symptoms as children that they no longer experience or vice versa. Having to think about these options can make the test challenging to complete, but do your best to select the most applicable option. Each of the four options has a different score value so accuracy counts on this one.

I often found that none of the four choices was exactly right because the questions tend to be phrased in an “always/never/only” format when what I really needed was a “sometimes” or “most of the time” phrasing. I also found it hard to answer some of the vaguer questions when it came to my childhood because my memories weren’t specific enough or I wasn’t a very self-aware child (which is a clue in itself, I suppose).

Scoring the Test

Each question is scored on a 4 point scale:

- 3 if the symptom is always present (or never present for “normative” questions)

- 2 if the symptom is only present now

- 1 if the symptom was only present in childhood

- 0 if the symptom was never present (or always present for “normative” questions)

If you take the test at the Aspie Tests site, you’ll receive an overall score plus 4 subscale scores. If you take it at the Aspergian Women United site, you’ll get only an overall score.

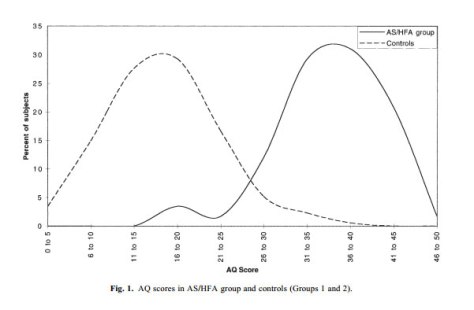

In the 2010 study, the scores for those previously diagnosed with ASD range from 44 to 227. The scores for control group members ranged from 0 to 65. The researchers set a threshold of 65, meaning that a score of 65 or greater “is consistent with a clinical diagnosis of ASD.”

It’s interesting to note that only 3% of the people with ASD had a score below 65 and 0% of the control group participants had a score of 65 or higher. There is very little overlap between the two groups, unlike the AQ study results.

In addition to an overall score, the RAADS-R provides 4 subscale scores. The creators of the test emphasize that the overall score is more accurate than any of the subscale scores alone, but the subscales are still informative if you’re curious about where your stronger/weaker areas are. The researchers also state that the RAADS-R is not intended to be administered outside of a clinical setting (such as online or by mail, both of which are valid AQ administration methods).

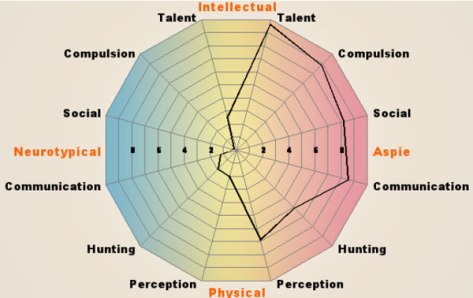

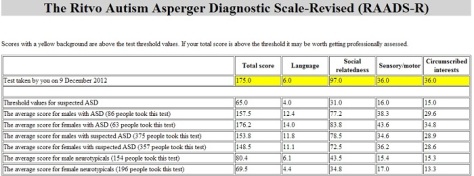

Here are my scores:

Total score: 175

Subscales:

- Language: 6

- Social relatedness: 97

- Sensory/motor: 36

- Circumscribed interests: 36

Any of the scores that are highlighted in yellow are above the clinically identified threshold values for ASD.

The averages given in the chart above are for people who took the test at the aspietest site. They tell you how you compared against other people who identify with the same neurotype as you, but little else.

The Bottom Line

The RAADS-R uses a slightly different approach than other autism screening instruments, making its use more appropriate in a clinical setting. However, it still provides an interesting snapshot of autistic traits for those who take it informally.