Aspies are notoriously unathletic. We tend to be clumsy and uncoordinated. Chalk it up to a motor planning deficit, poor executive function, proprioception difficulties, dyspraxia, or all of the above. Whatever the cause, the result is that we’re more likely to be branded a geek than a jock.

Unfortunately, I never got the memo on this. All my life I’ve loved sports and being physically active. Loving sports, in my case, isn’t the same as being good at sports, but I’ve never let that stop me.

Though my parents didn’t know I had Asperger’s they did know that I was clumsy. One of their nicknames for me was “Grace”–as in, “careful there, Grace” and “that’s our daughter, Grace.” I think this is funnier when you’re the one saying it than when you’re the one tripping over an inanimate object.

Perhaps in an effort to help me overcome my lack of coordination, they signed me up for a lot of individual sports: dance, gymnastics, bowling, golf, diving, swimming, karate.

Most of these were activities that I could do with other kids but didn’t require the type of interaction that team sports do. I was on a bowling “team.” All that meant was that I took turns with four other kids. The bowling itself was an individual pursuit. Other kids took a turn. I took a turn. I got to add up the scores. I wandered off to watch one of the arcade games. Someone called me back when it was my turn. It was great.

Golf and dance and karate were the same. I did these things alongside other kids but not really with them. There was an appearance of social interaction. The actual amount of interacting I did was minimal and that was fine.

I’ve always loved individual sports for exactly this reason. I learned to swim soon after I learned to walk. My family had a swimming pool in the backyard so I was in the water months after being born and enrolled in swim lessons as soon as the YMCA would take me. Swimming is still one of my favorite ways to relax. I love being in the water–the sensation of weightlessness, of gliding, of floating, of being surrounded and suspended–and I love the rhythmic movement and sensory deprivation of a long swim.

As an adult I took up running. Like swimming, I enjoy the rhythm of running. I also like the way it gets me out into the quieter places–trails through the woods, quiet paths along the river, a beaten single track frequented more by deer than humans. I loved long bike rides as a kid for the same reasons.

The Beauty of Individual Sports

I tried team sports. In middle school, I was on the school softball and basketball teams. It was fun but I wasn’t very good at it and spent most of my time sitting on the bench during games. I also got razzed a lot by coaches for not making enough effort. My basketball coach was always yelling at me to be “more aggressive” but I had no idea what she meant.

There was a lot about basketball that I didn’t quite get. Team sports have many variables–the rules, the other team members, the fast pace, the ball (inevitably there’s a ball involved). For the typical aspie, this is a lot to manage. By the time I got to high school, I knew that team sports weren’t for me.

But individual sports! This where aspies can shine. When I’m out on the trails or in the pool, I feel strong and athletic. I feel like I’m coordinated and connected to my body. I feel like I’m good at a sport! Forgive my exclamation points, but this is exciting for someone who grew up feeling clumsy.

So, let me sell you on the wonders of individual sports for aspies of all ages:

1. You can progress at your own pace. Individual sports allow you to measure your progress against yourself. While you might compete against others, most individual sports also encourage “personal bests.” Running a new best time for a mile or swimming a personal best for a 400 is as fulfilling as beating an opponent. Maybe more so, because it’s an indication that your practice is paying off and you’re better at your sport than you were a month ago or a year ago.

2. You can be part of a team without the pressures of a team sport. Individual sports can be less stressful than team sports when it comes to having to perform well every time. If you have a bad day as a team player, your actions can impact the whole team. If you have a bad day as a cross country runner, you might not place well, but one of your fellow runners could still win the race. There are team consequences, but they tend to be less severe.

3. You can practice by yourself. This is a huge advantage for aspies. Because of our motor coordination issues, we might need a lot more practice than the average person to learn or master a skill. When that skill is something that doesn’t require a team or a partner to practice, we can spend hours working on it alone, at our own pace.

4. You play side-by-side with others. Team sports put a big emphasis on bonding with other team members, which can be stressful for aspies. Individual sports allow you to play alongside others, interacting as much or as little as you feel comfortable.

5. Individual sports tend to be rhythmic, repetitive and predictable. And what do aspies like more than rhythmic, repetitive, predictable movement? Running, cycling and swimming are like large-scale, socially acceptable stims. And you can do them for as long as you like. The more, the better!

6. Individual sports can burn off a lot of excess energy. Many individual sports are endurance based, making them an ideal way to tire out a high-energy aspie. Even moderately vigorous physical activity will burn off excess energy and trigger the release of endorphins, which not only improve your mood but can reduce anxiety and help you sleep better.

7. Individual sports improve coordination. All sports improve coordination, but individual sports tend to be more “whole body” sports, requiring you to integrate all of the parts of your body to achieve the best possible result. Think of the type of movement required for swimming breaststroke versus the type of movement required for playing shortstop.

Why Exercise is an Essential Part of Managing My Asperger’s

I need to get in at least an hour of running, swimming or walking every day. I need to exercise every morning. When I say need, I’m not kidding. If I didn’t exercise religiously, I would likely be on medication for both anxiety and depression.

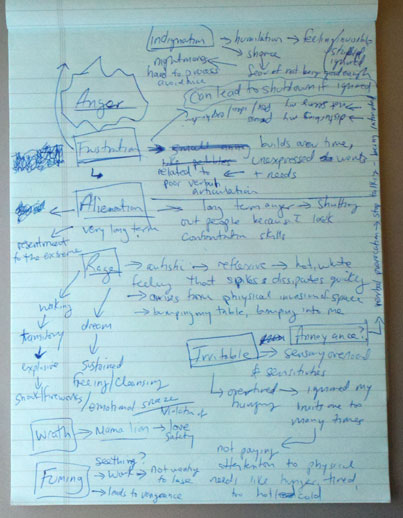

Hard physical activity burns up the unwanted chemicals in my body and generates a nice steady flow of good chemicals. Exercise takes the edge off my aspie tendencies and leaves me feeling pleasantly mellow. If my physical activity level falls for a few days in a row, I start feeling miserable. I get short-tempered, cranky and depressed. I lose my emotional balance. I don’t sleep as well. I find it harder to focus.

Being physically active also keeps me connected to my body. I have a tendency to retreat into myself and become disconnected from everything that isn’t inside my head. I’m also still–in spite of decades of sports practice–more clumsy and uncoordinated than the average adult. Being physically active helps me combat this and makes me more physically resilient when I do take an expected tumble.

A Little Different Spin on Physical Activity

One of my favorite bloggers, Annabelle Listic, has written a wonderful post–Kinect with Me!–about how she is using the physical activity of gaming to address some of her concerns (which are different from mine). I’ve never played a video game that requires physical interaction but her post got me thinking that this type of gaming might have many of the same benefits as participating in an individual sport.