A few words of preface to this piece: I grew up as undiagnosed autistic with a gifted label, so my experience is different from what doubly exceptional children today experience. There were no social stories or social skills classes when I was a kid. Asperger’s Syndrome didn’t become an official diagnosis until I was 25. If you’re younger than I am and grew up with the doubly exceptional label or you have a child who is doubly exceptional, I’d love to hear about the differences or similarities in your/their experience.

—————-

Remember how, back when you were in school, there was one day of the week that was better than all the others? Maybe it was pizza day or the day you had band practice or art class. There was always one day that you looked forward to all week, right?

In sixth grade, for me that day was Friday. On Friday, I got to leave my regular classroom and walk down the hall to the TAG classroom. TAG stood for Talented and Gifted–a town-wide pilot program that accepted two sixth graders from each of the five elementary schools in our small suburb.

Ten geeks, eight of whom were boys. Ten kids who happily poured over reference books on Blitzkrieg and backgammon while the rest of the town’s sixth graders were wrestling with the math and reading curriculum we’d finished the year before.

Looking back, in addition to being gifted, most of us were probably on the spectrum as well. We were all socially awkward to some degree. None of us had to be asked twice to choose a topic for our Type III independent research projects. We came to class lugging backpacks filled with resources. We had entire libraries at home on the subjects we wanted to explore.

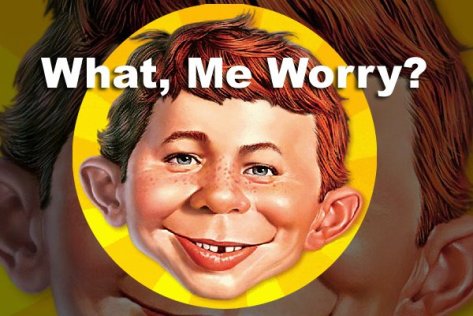

No matter what we asked to study, Mr. M, the aging hippie who taught the class, encouraged us. When I told him I wanted to “study” MAD magazine for my second project, he explained the concept of satire and helped me work out why the comics were funny.

TAG was aspie heaven. If I spent the afternoon curled up in a beanbag with my stack of MAD magazines, no told me to return to my seat. If I was the only kid in the class who brought a bag lunch because I couldn’t stomach the school pizza, no one at the lunch table made fun of me. If I needed to have a joke explained, even a whole magazine full of them, there was Mr. M, sitting at his desk, ready to patiently answer our questions with humor and honesty and not an ounce of condescension.

He thought we were the coolest kids around and in that classroom, we thought we were too.

Doubly Exceptional

Today, kids like the ones I shared the TAG classroom with are labeled doubly exceptional or twice exceptional. Back then we were the geeks and the nerds. Particularly if you were a girl and you were smart, people seemed to expect you to be weird. “Normal” girls weren’t smart and smart girls were quirky.

Adults wrote off our quirks as a byproduct of our intelligence. They sent us out to the playground and expected us to figure out how to navigate the social minefields that lurked within kickball games and jump rope circles. We were smart. We would get it eventually. When we didn’t, they reminded themselves that we were smart and because we were smart, we would get by.

And we did, but not always in the way they hoped we would.

As the concept of giftedness evolved, some theorists put forth the idea of giftedness as “asynchronous development,” suggesting that gifted children reach intellectual milestones faster than other children but lag in cognitive, social and emotional development. Proponents of this theory say that children who are hyperlexic, for example, develop in a fundamentally different way because they have access to advanced ideas at an earlier age than other children.

While this may be true of some gifted children, for many it serves to shift the focus away from their developmental disability–explaining it away as a byproduct of their giftedness. It’s easy to look at this model and assume that these children will just magically catch up with their peers developmentally. After all, they’re smarter than their peers. What’s keeping them from being just as adept in the social and emotional realms?

This is a bit like taking a kid who’s a good baseball player, throwing him in the pool, then being surprised if he sinks like a rock. What do you mean he can’t swim? If he’s athletic enough to hit a baseball, surely he’s athletic enough to swim.

Does my metaphor of a drowning child seem extreme?

If you spent your recesses and bus rides and summers at camp getting mercilessly bullied, physically threatened or worse, you probably wouldn’t think so. For kids who are developmentally disabled but intellectually gifted, expecting them to get by on intelligence alone is the equivalent of throwing them in the deep end of the pool without teaching them to swim first. It’s leaving them to drown–emotionally and mentally–all the while telling them how smart they are.

When a Strength Isn’t Always a Strength

Not that encouraging intellectual strengths is a bad thing. Unlike kids labeled developmentally disabled and given a deficit-based course of therapy designed to “fix” them, doubly exceptional kids have an advantage in their intelligence. It allows them to mask a huge portion of their disability.

Oh, wait–is that really an advantage?

Masking our disability with coping strategies and adaptations means that when we fail to hide something, people assume we’re not trying hard enough. Or we’re being deliberately obstinate. Or that we’re lazy, defiant, insolent, shy, ditzy, or scatterbrained.

“What’s wrong with you?” they ask incredulously. “You can memorize the batting averages of the entire Major League, but you can’t remember to put your homework in your backpack?”

And so the doubly exceptional child grows up thinking, “If only I tried a little harder . . .”

No matter how hard she tries, the refrain never changes.

Can’t hold down a job. Can’t finish a degree. Can’t maintain a relationship. Can’t seem to do the things an average adult can do.

“What’s wrong with you?”

If only I try a little harder . . .

Now What?

There is no gifted class in adulthood. No one cares if you can memorize all 20 spelling words after looking at them once. You don’t get to escape life on Fridays, reading MAD magazine while the sounds of the playground drift in through the open windows.

When you arrive in adulthood lacking the social skills that most people have mastered by sixth grade, life becomes exponentially more confusing and hard to navigate. For much of my adulthood, I’ve had the odd belief that someday I would “grow up” and suddenly feel like an adult. That I was just a little behind the curve when it came to social skills and one day everything would magically fall into place.

I don’t know when or how I was expecting this to happen. It’s illogical. Maybe it stems from the belief that social skills are intuitive rather than a skill set that needs to be learned.

Neurotypical people acquire social skills primarily by absorption; autistic people need to be taught social skills explicitly. When we’re not, we’re no more likely to learn them intuitively than a typical person is to pick up algebra intuitively.

Maybe that’s where the problem lies. Adults often assume that if a kid is smart enough to learn algebra in elementary school, he or she is smart enough to figure out social rules too. But who would expect the reverse to be true? What rational adult would say to their kid, “you’re smart enough to find friends to sit with at lunch, why can’t you figure out how to solve this linear equation yourself?”

I (Actually Don’t) Know What You’re Thinking

Even as I write this, I find myself cringing internally. Do I sound like a whiner? Shouldn’t I be thankful for the advantages my intelligence gives me?

Again, I find myself arriving at the notion that if I just tried harder, just applied the intellectual resources I have, I’d be fine.

Yes, intelligence helps. In particular, it helps me identify patterns and come up with rules–rules that any neurotypical adult could tell me, if I asked them.

If I thought to ask. Which I often don’t.

For example, at a get-together at a neighbor’s house, I accidentally knocked over a wine glass. The glass broke; I apologized.

For example, at a get-together at a neighbor’s house, I accidentally knocked over a wine glass. The glass broke; I apologized.

Years later, while reading an etiquette book, I learned that I should have offered to replace the glass. This sounds like common sense now, but it’s not a rule I would have intuited or even thought to ask someone about.

Perhaps this is why the invitations for drinks at that neighbor’s home abruptly stopped? Did they find me insufferably rude? I have no idea.

Worse, when I mentioned the rule to my daughter, she frowned and said, “You didn’t know that?”

There are hundreds of unwritten social rules like this one. I have no idea how people learn them. Perhaps they don’t. Perhaps after a certain point, it becomes all about the dreaded perspective taking. You break a glass and think, “If I were the hostess, what would I want my guest to do to make this better?” And the obvious answer, when I think about it like that, is “offer to compensate for the loss.”

One Rule at a Time

Generally, I learn a social rule by reading about it, having someone explain it to me or seeing it in action. Unfortunately, many rules are executed privately, so there is no chance for me to observe them. The polite guest gets the hostess alone in the kitchen and asks about the cost of replacing the glass. (So says Emily Post.)

Even more frustrating: I’ve had people offer to replace something that was broken at my home. To me, that rule is, “If a guest breaks something in my home, they’ll offer to pay for it.” I don’t instinctively reverse the rule to apply to myself as the guest. If you’ve heard it said that autistic people aren’t good at generalizing, well, there you go.

There’s something at work here that has nothing to do with intelligence.

I’m smart and I’m developmentally disabled. One does not cancel out the other.

Oh, thank you, thank you, thank you! This is my life, too. You were lucky to be diagnosed at age 25. I finally figured out I was Aspie at age 54. Too late to do much about it, really, except try to accept who/what I am.

I can’t remember learning to read because it seems I’ve always read everything. When I was a kid, I was reading Shakespeare at age 11, because I liked it. I read The Complete Sherlock Holmes by A. Conan Doyle at age 9, because I liked it. When I was 10, I read every book by Mark Twain I could get my hands on one summer while sitting in our grapefruit tree in the front yard. On the other hand, learning how to tie my shoes brought me to tears, and I can remember having a meltdown, probably around age 4, trying to learn how with a woman who was very impatient with me. She didn’t understand why I couldn’t tie my shoes.

Unlike you, though, I was not allowed to go to the gifted class in 6th grade, even though I was reading Shakespeare, because I wasn’t doing so well in math. Imagine! I felt so punished. Math just seemed to be a bunch of arbitrary numbers and letters with no practical application, so I couldn’t figure out what to do with it once I started pre-algebra. I remember being told that I would have to stop using “big words” with the other kids so they would like me. I was “weird.” Finally in high school I was allowed to do special projects – like being the assistant to the botany class and doing classifications of lake algae – because I was interested in the subject. I had some great teachers who let me pursue my interests. I managed to memorize the pages of the algebra book long enough to pass the tests, then promptly forgot everything I had learned, but it was enough to get me good scores on my SAT and get into college, where I took advanced English courses at the same time I was taking “remedial” math. Ugh!

Later, when I went to college, a senior asked me why I was taking a Shakespeare 405 class in my first semester as a freshman. He explained that it was a “400-level class.” I totally didn’t understand what he meant. I liked Shakespeare, so why wouldn’t I take a class in his works? “But it’s a senior-level class,” he explained. Oh… well, nobody had said I couldn’t take it. I stayed, and I aced the class and the Shakespeare 406 class the next semester as well. Did I say I liked Shakespeare?

Yeah, being smart has allowed me to compensate somewhat for my lack of understanding of social expectations – that and a strong English upper-class upbringing in which the rules were very clearly delineated in a way they are not where I live now in Wisconsin, which I find incredibly frustrating. So because of endless years of repetition, I behave a little like a Victorian English woman, the formality of which probably causes some amusement among people who meet me, since they frequently remark that I must be from “somewhere else.”

BTW, has anybody ever considered the possibility that Sherlock Holmes would have been an Aspie? Someone must have said it, surely.

You’re welcome! Thank you for taking the time to comment. I was actually diagnosed at 42. At 25 I was a mess and probably would have been diagnosed with a half dozen things that weren’t ASD. I don’t remember learning to read either, though I think I went to kindergarten already knowing the basics. I’ve been a reader for as along as I can remember and was usually reading stuff way too “advanced” for me.

It’s interesting that you mention your upbringing as helping you pass in society. I was also raised in a family that had clear rules for behavior and I definitely think that contributed to my being able to get along with getting into too much trouble at home.

There is a great deal of talk in the Sherlock fandom (which some of the folks I follow on Tumblr are part of) about Sherlock’s possible aspie-ness. The BBC adaptation actually has Watson use the term Asperger’s in reference to Sherlock once, So you’re probably on to something there. 🙂

Oh, and I just love the “new” Sherlock series. Never mind that Benedict Cumberbatch is so dishy. If Holmes was living now, that’s just what he’d be like.

Sherlock season 3 is back on this January!!! So excited!!! xD

Julian Barnes in his novel “Arthur and George” (2005) is giving his opinion on the aspieness of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

I am actually writing an essay on Sherlock Holmes and Asperger’s…:D

Not sure if you know, but aspects of Sherlock Holmes’ character is actually based on a real person. Worth a look: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Bell

There’s a good quip here that talks about how Bell’s “method” inspired the literary tropes in the books: https://www.irishexaminer.com/viewpoints/analysis/fiction-imitates-real-life-in-a-case-of-true-inspiration-172752.html

Its hard to say if he was aspie, or just had a really good set of skills. I suspect a bit of both. Since learning about it, I’ve been able to use my own autistic attention to detail skill along with some memory techniques from old oratory practices ( https://www.ted.com/talks/joshua_foer_feats_of_memory_anyone_can_do ) to emulate it a bit. I still “can’t remember to put my homework in my backpack”, but my recall for facts and figures has become more useful.

The one thing I can say for certain is that the higher level of anxiety seems to be a partial cause for the attention to detail being easier – stress (and particularly cortisol) seems to lead to a stronger memory encoding baseline.

Oh goodness! This is so much like my own experience that it’s scary. It sounds like we are about the same age and went through similar school systems. When I was a kid, the one word that I learned to hate more than any other was the word “potential.” It was the word that was used to tell me how disappointed people were in me because I obviously wasn’t trying hard enough. I can’t count how many times I was “thrown into the deep end” and left to drown because I was “obviously too bright to need help.”

I may come back and comment more, but right now the memories and feelings are overwhelming.

John Mark McDonald

Scintor@aol.com

I’m sorry you found this overwhelming. It was hard to write because I go back and forth between thinking my intelligence makes me privileged and thinking it just handicaps me in different ways. Potential is a hard word to swallow when it’s delivered in “that tone” and it looks like many of us aren’t very fond of it.

Easiest way to use your intelligence to get round social problems… read books on body language, anthropology and etiquette. I am very grateful to Desmond Morris and drama classes for teaching me to recognise and mimic physical social cues. Though I don’t think it would have helped with the broken glass scenario.

Sadly its not exactly easy to put things read into practice and its often not enough to be told. I am glad that there are such things as social skills classes in the world and hope that they include teaching people to have patience with those who don’t automatically do what you expect them to do in a situation.

I recently read Emily Post’s giant etiquette book nearly cover to cover. It was very helpful. Manners are basically social skills/social stories for adults, I guess. I made a lot of notes as I was reading because I found some helpful scripts for difficult social situations–like how to firmly but politely decline something, how to enter into a conversation, how to start a conversation with a stranger, etc. It’s definitely harder to put things like that into practice than it is to learn the basic rules, but I think it gives me some additional confidence to have some scripts to fall back on in times like that.

My reports from school, and my evaluations of decades of work, all said the same thing. “So smart…if you’d just *try*! “The only thing holding this employee back is herself” (that really hurt), “Does not work up to potential.”

The “drowning child” image is spot-on. It sure FELT like I was trying really hard, but nobody had taught me to swim…

I was in my teens when I ran across my sister-in-law’s book on etiquette for an officer’s wife (my brother was in the US Army). I devoured it, and thought it was so cool that there were instructions to at least some parts of life. I wish I didn’t have to be so conscious of “when people do X, respond with Y” but I do like having some rules to follow.

I didn’t have a “pizza day” but I had an early Christmas…in my senior year of HS, I was failing some stupid mandatory class. To get me enough credits to graduate, the school shoved me into 3 English classes in one semester, one of which was advanced. They figured maybe I could get enough Ds to get the needed credits.

Best semester ever. Interesting schoolwork (finally) and people pretty much left me alone because it was such an odd situation. And I had an excuse to hyper-focus on things that interested me, and not spend time trying to fit in.

I finally made A’s that semester. Not many friends, but some A’s. Maybe I learned something about what I could do if I could put “socializing” energy into focused work.

What I really want to say about the people who wrote those evaluations would be sweary and inappropriate. 🙂

It’s kind of a consolation to read an etiquette book and realize that there are a lot of other (presumably NT) people who don’t know what to do in certain situations either. I was amazed at how detailed and specific Emily Post gets. They’ve literally thought of everything and then some. It’s a pain in the ass to have to approach it as an “if . . . then” equation, but you’re right about it being helpful to at least have some idea of what the appropriate response is.

In my last semester of high school I took all English electives plus “Senior Morality” (which was required and which I almost failed because I’m so stubborn) because I’d finished all of the other required courses. My guidance counselor warned me against how it would look on my transcript to be ditching pre-calc and some AP science class she wanted me to take but I had a blast reading all those books and was beyond caring. It’s funny how we remember those classes as being highlights of high school. Sounds like they were a refuge and then some for you.

Memories coming back from reading all the fascinating accounts:

In hindsight I may have been extremely lucky to get a book on etiquette at age 8 (?) which I read at least five times. Not because it was interesting (it wasn’t) but back then I simply did not have enough books for my voracious appetite, reading *everything* more than once, in this case unwittingly absorbing helpful social clues. Like: greeting adults properly instead of mumbling something unintelligible or turning in the approximate direction of people you talk with and not orienting you body sideways. Or learning to look at least at the *chin* of somebody during a conversation instead of in the eyes. Almost nobody notices my lack of eye contact till today. Said book may have helped more than many hours of counseling …

My brother, just two years ago, sat me down and said how sad it was that “you haven’t lived up to your potential.” I am 48 and very smart. I was diagnosed with Asperger’s three months ago. I’m still trying to figure out what is acceptable and how to behave as an ACTUAL autistic person, rather than as a weird normal one.

This blog post and the replies that follow are like balm on a burn.

People are always telling me that I am hard on myself, which I don’t totally understand, but if I am it is exactly because I think, hey I am supposed to be an intelligent, creative person; so why do I mess up all the time? Why can’t I do this thing that other people can do? Am I lazy? Am I secretly stupid? I had better hide it.

Now that people know that I have Asperger’s the comment is usually, but your’re so GOOD with people!

Yeah? I am good with people, but people are not good for me. I am smart and it helps me fit in and get by. It dosen’t help me on the inside though. People think I am hard on myself – they have no idea how much torture I am usually in in order to function in the world.

But you folks do. You do, you get it, you experience it and you share that experience. So as Badger said, “thank you, thank you.”

Yeesh. Sorry you had to hear that from your brother. Doesn’t seem like it’s any of his business, for one thing. 🙂

I’m glad you found this helpful and that this place and the people here are comforting. It was tough to write this piece and I’ve been holding it for a while. The “but you don’t seem that autistic” comments are the worst. Well, yes, because we’re all making a hellacious amount of effort and have been for as long as we can remember. I have no idea how people expect us to respond. I suppose they think it’s a compliment.

I could have written this myself. I was in special programs for smart kids. Skipped a year in math. Took all the Honors classes I could get. English was always boring to me when they were teaching grammer but literature was so much fun! I was also painfully awkward in social situations. I barely spoke to anyone. My best friend remembers the first time she met me because of something completely out of context that I said to her in Kindergarten. She also remembers me not recognizing her until I had been around her several times and began to recognize her by her shoes.

I was bullied. Picked on. Verbally abused. Physically abused. I was beat up and tortured on the school bus almost weekly. People thought I was weird, nerdy, and extremely shy. My teachers would tell my parents that I “would have so much potential if (I) would just come out of my shell and speak to others” instead of spending my time with my nose in a book. I used to get in trouble for bringing “adult” (which meant well above grade level) books to class and reading them inside my textbooks but still knowing what was going on in class.

I had a few teachers who saw who I was behind my long hair and they did what they could for me but most of the time I was the student who got good grades but never volunteered to answer in class and just blended into the desk. I didn’t do anything to stick out. I didn’t do anything to call attention to myself because I hated to have everyone looking at me. The school bell would always scare me when it went off and fire drills and pep rallies were a special kind of torture for someone who hated crowds. The only thing I liked about a pep rally was when everyone would stomp to We Will Rock You because it vibrated the bleachers in a pattern I liked. 🙂

Anyways, I completely understand. I got my diagnosis at 31 so I feel you on no one really knowing what to do with me most of my life.

“come of my shell” — boy does that bring back bad memories. My teachers used the exact same words. I was exactly like you, blending into the background. Teachers often didn’t learn my name until November, especially once I got to the upper grades and had a bunch of different teachers, each for one class per day.

And I got into so much trouble for reading “adult” books, except that mine really were quite adult. I read “Amityville Horror” in third grade (I remember looking up “pubic hair” in the dictionary and then being shocked for days at the concept!) and most of John Irving’s books in middle school. 🙂 I have no idea where I got them, though. Maybe at the town library or pinched from an older cousin. I remember not getting to finish a few books because my mother took them away from me when she discovered what I was reading.

Your story about your best friend is adorable. It’s amazing that you’re still friends. 🙂

I used to read a lot of poetry books, mythology, anything that had an interesting title I would pull off the library shelves and take home. I always checked out my maximum allowance of books when we went to the library and that was almost weekly. My mom gave up trying to keep me in the children’s section when she saw that I could burn through those types of books in one or two evenings. She has always encouraged my reading though and she wanted me to learn as much about language as possible. I sometimes wonder is she wasn’t trying to give me a bigger “mental library” to pull from for when I couldn’t find my own words?

My best friend lives several states away from me now but we make it a point to catch up with each other on a regular basis. She stuck with me so long because she was one of the few people who knew I was quirky and didn’t really care. She likes me for me. 🙂 When I got my diagnosis, she basically said she knew all along that I had something going on but she didn’t have a name for it back then. LOL She’s pretty awesome and one of very few people who still “keep up with me”.

I can’t remember ever getting books from the children’s section. Oh man, just thinking back to childhood I can actually smell the old library–the one that occupied half of the police station building before it was moved to a big new library across the street. Thank you for that. 😉

When I told my best friend from childhood (who I still keep in irregular touch with) about my diagnosis, she didn’t see very surprised at all and mentioned that her littlest one was sitting on her lap stimming as she was emailing back. So, yeah. It’s cool to know that we have those precious people in our lives who are around for the long haul.

I’m just so overwhelmed by finding this, I can’t post properly tonight. I would like to point out, although I’ve only read about 50 posts, in which I found my people. I’m only missing one comment that I always received which was ‘I can’t believe that you said that’. Such that, at an early age, I learned to ask the questioner why they would question their own ears

Thank you for letting me know that you’re reading and you’ve found a lot to relate to here. I hope you’ll comment some more when you’ve had time to process your thoughts. 🙂

Wow, that was scary to read. It was just so shockingly similar, and I know many comments above mine say the same thing. In 5th grade, I was placed into the gifted and talented class (I was always in the higher math class in elementary school anyway). I liked the logic puzzles the woman would give us, but I quit… because it broke my routine. Somehow this should have set off some red flags that a ten year old is freaking out over not being in her English class because another class disrupts the time slot. I think my family is still expecting that suddenly I’ll catch up, and maybe when they finally realize that it isn’t happening, they’ll believe that I have aspergers. Much like the old school beliefs, to them I am gifted and will eventually be like everyone else or I am choosing not to be. I’m always worried that I’m lacking. Academically, I blow people away. I’m double majoring, in the scholars program, and am in 3 honors societies, but I lack friends and a life outside of school. I have a boyfriend, he hangs out with his friends, I stay home even though I am invited. My cousins, who are my closest relatives, go out with their friends all the time, and I worry that in the future, I won’t be able to get a job. I’m working on becoming a writer and getting things published, so I can make money in a way that works for me. It’s a long shot, but my professors say I’m talented, and they’ve seen a lot more in me than I have seen in myself. What I find most difficult is to appear so normal and be so different.

Oh, I completely understand why you would quit the gifted program if you were missing regular work. By the time I got put into the gifted class I had completely finished the school’s math and English curriculum and mostly spent my days making trouble and being kept busy with independent projects or being sent out to “help” the reading specialist, the main office secretaries, the librarian, etc. If I thought I was missing stuff, I would have had a harder time being out of the classroom for a whole day every week.

My elementary school was a progressive seventies hippy sort of educational experiment where we had grades 1-3 in one big room with five class areas (grades 4-6 were in another big room). We were officially in a grade, but were placed in learning groups according to our level. So I finished the 1-3 curriculum by the end of my 2nd grade year, but my parents refused (rightly) to let the school skip me from 2nd to 4th grade. I can’t even imagine the social disaster I would have faced landing in a huge room full of much older kids.

Your goal of being a writer sounds like a good one. I’ve been self-employed since shortly after high school and doubt I would do well in a conventional workplace (i.e. one where I’m not in charge or able to work alone). I’m guessing you’re aiming for a fiction career? Even if that doesn’t become feasible right away, I think if you can write well, there are a lot of nontraditional options for making a living. Making the transition from school to life can be a little rough. I didn’t got to college after high school so the “time to be an adult” learning curve was pretty steep. Having those college years to prepare and having a plan is going to give you a good head start on a career, especially since you have people who believe in you and hopefully will mentor you a bit.

I’m rambling! Sorry!

I love rambling and am fluent in it. I wish I had your hippie-style school. I was always ahead of everyone else, but I was told to read when I was finished to wait for the others to catch up. I think that’s how I read every Judy Blume book and another series involving a vampire bunny that sucked the life out of vegetables. Anyway, I want to write fiction, particularly science fiction, fantasy, etc. I have a wattpad account where I’ve been posting my story for my project http://www.wattpad.com/story/4527989-the-earl-of-brass I seriously think the college setting is great for aspies, a lot of independent study opportunities and a chance to study your favorite subject area. Nerd’s the word.

Thanks for the link – I’ll check it out! I got assigned lots of independent reading too. I loved Judy Blume and S.E. Hinton and the Nancy Drew series. I’ve never hear of the vampire bunny series, though. 🙂

College, though I went really late, is definitely aspie paradise. I think most of the econ department was on the spectrum. No one found it odd that we all arrived 15 minutes early for class and then basically ignored each other unless someone started a conversation about the class material or told math jokes. Yay nerds!

It can be so exciting and heartwarming to rummage through older posts (happy flapping and all)!

Reader, if you arrive here after going through the exchange between thevampirelock and Cynthia on self employment and the idea of becoming a writer, follow the link above! thevampirelock has her first novel out only one year later. Five stars on Amazon plus a Writer’s Award!

Oooh! Bunnicula! I remember those stories! 😉

I had problems when I went to university because I had no idea I was Aspie, so had no way to get supports I needed for dealing with uni life. Got through one semester (sort of, kind of, ended up failing all classes despite my intelligence), and haven’t really been back since. Tried a community college (trade school for those not Canadian), and got 1-1/2 semesters done, but then the February seasonal affective disorder hit, and boom, there went my schoolwork! *sighs*

Anyway, have fond memories of the Bunnicula stories. Not quite as fond memories of Judy Blume, though I read most of them – I just wasn’t as interested in “real life” stuff as I was in SF and fantasy.

Will check out the wattpad story!

😉 tagAught

I am a generation younger than you and this mirrors my experiences quite a bit as well, though my parents pushed quite a bit to keep the “autism” label away from me in grade school. I was constantly told “you’re so smart, why can’t you do xyz?” – that question still terrifies me today. Right now I live in aspie heaven – I’m a PhD student in a lab with an amazing advisor who supports me and my quirks and allows me all the time and space I need to thrive. But yes. This is just so accurate for so many of us, even the younger ones. Thank you for writing it. 🙂

It seems like people even more than one generation younger had similar experiences. I do know that a lot of states have doubly exceptional guidelines for their gifted programs, but maybe this is very new? Academia is definitely aspie heaven for many of us. It’s so good to hear that you have a supportive advisor.

I loved college even though I didn’t start until I was in my late thirties. The econ department turned out to be full of people like me. It was quite a revelation. 🙂

I definitely never knew about the wine glass rule. Thank-you for letting me know! My cat owes me a wine glass now (heh)

The rules of the neurotypicals drive me bananas. They often seem like common sense as you’ve said AFTER someone explains it to me. I don’t often realize it on my own. I remember a time when I was small and I cried because I couldn’t have desert because I hadn’t eaten my dinner. Well my mom was perplexed as she never said a word about a rule like this, where did I learn it? Bewitched, The Cosby Show or The Brady Bunch I suppose.

We had a very strict rule about swearing in my house. It simply wasn’t tolerated, in fact I never once did it. But in second grade, my teacher asked me “What does a vacuum do?” And I answered “It sucks” and then burst into a fit of hysterical tears. My teacher was flabbergasted. I remember her handing me packets of stickers and telling me that it I didn’t stop worrying like I did Id have an ulcer before I turned twenty- all because I said a swear word. Context has been a struggle for me my whole life and that is a perfect example of how my brain confuses rules.

I think as Aspies we have our own rule book and to NTs it might seem like non sense but I still don’t get why I’m Supoosed to say “God Bless You” a second or third time if someone has a sneezing fit 🙂

It’s so annoying when the rule seems obvious after someone lays it out. I bet you got your dessert rule from the Brady Bunch. It sounds like something Alice would say. 🙂

The way you internalize rules reminds me a lot of myself as a kid (and still, in a lot of ways). I had a strict set of inner rules that seem to go beyond what adults actually expected of me, but I had such a hard time knowing what was expected that I erred on the side of caution a lot.

Are you really supposed to say “God Bless You” more than once? I didn’t know that. There needs to be a rule clearinghouse where we can pool our knowledge about this stuff.

There needs to be a rule clearinghouse where we can pool our knowledge about this stuff.

Your dessert story reminds me of when I was in kindergarten and turned six years old. I walked straight up to my teacher and said, quite firmly, “I’m six. I’m ready to go to first grade now.” She told me I had to stay in kindergarten. I was furious. Six-year-olds got to go to first grade, and I had to stay behind with these babies who couldn’t even READ??? I had a meltdown right then and there. I can still remember how mad I was, though I’m writing this with a smile on my face.

I had a similiar experience! In TENTH grade my Spanish teacher told me “Why don’t you just go to Honors then?” And then three days later the teachers had a conference and my teacher said I had been skipping class for three days. This was shocking – until the Spanish 3 Honors teacher spoke up and said “She’s been in my class” Ha! I wasn’t being defiant. I had no clue he was being sarcastic, they let me stay in the Honors class, probably as a punishment haha. I did horribly in honors

That honours class mistake made me cringe in recognition! I eventually went to the extreme of asking for clarification on every instruction I was given regardless of how straightforward it seemed. So if someone told me the pass the salt, I’d probably say something like “You want me to give this salt shaker to you right now?”. This led to much fewer misunderstandings, until I got a teacher who believed in ‘ask a silly question, get a silly answer’, a philosophy which seems designed to traumatise autistic spectrum kids out of ever asking any questions at all! 😦

These days I think I’ve got better at finding a balance between asking clarifying questions and potentially making incorrect assumptions. I do explain myself and ask clarifying questions a lot more than I think most people would, but I think I do this in a way that looks like ‘active communication’ and so can be taken as a positive trait and a sign of attentiveness, rather than being intentionally annoying or somehow insulting (although new people do sometimes seem to manage to take it this way).

My son is currently in 4th grade and, socially, school is so difficult for him with constant stumbles and falls. I’m afraid he doesn’t even try much any more because doing so draws attention to himself and his adult vocabulary and ideas. He is diagnosed PDD-NOS although, when my husband and I first noticed he could read at age two, I simply settled on the certainty that he was a genius (I still think he is). As a mother, I am so frustrated with the lack of social skills help at school, the place where he needs it most, because he doesn’t generalize his skills learned in social skills groups. I don’t know what to do anymore but I worry that the effects of social isolation will affect his mental health more than being in school will help his social skills. Sometimes I just want to pull him out and homeschool him but I’m working. Thank you for sharing your story and to the commentors also. It helps to know the perspective from those of you who have lived the experience.

Your concern about your son censoring himself to avoid drawing attention to his intelligence really hits home with me. I learned early on that “no one likes a smarty pants” which is I guess how I came across to many people. I probably still do at times. We aspies tend to have a lot of knowledge and a need to share it.

It’s interesting that you mention him not being able to generalize from social skills groups to real life social interactions. I’ve wondered about this for a long time. There are many cases where I know in retrospect that I made a social gaffe but I just wasn’t able to process quickly enough in the moment to “override” my natural response. I think, in terms of mental health, the most important thing you can do for him is to constantly let him know that you love him just the way he is, social stumbles and all. It’s hard being different but having a place where you can feel loved for being your odd self–whether that place is home or my beloved TAG classroom–goes a long way toward making a kid feel good about themselves.

I’m so glad I found your blog! I love the way you write and I can relate to your experiences completely.

Thank you! I’m glad you found it too. 🙂

“The “but you don’t seem that autistic” comments are the worst. Well, yes, because we’re all making a hellacious amount of effort and have been for as long as we can remember. I have no idea how people expect us to respond. I suppose they think it’s a compliment.”

When I read that it just makes me want to scream (in a good way). It takes quite a lot of courage to come out and say that I have Asperger’s and then when someone responds like that it just makes me feel like I have been slapped down somehow. It’s like they want you do be ‘normal’ because to acknowledge that you are different means that they have to accept that you are struggling, and that means that they will need to make some kind of extra effort for you. And people really do like to put themselves first most of the time. (Which is stupid because if everyone put everyone else first, everyone would be taken care of. So obvious!)

Ho hum.

I vote a stupendous round of applause and mutual back-slapping for all the autistics who try to be integrated in the world (and of course support and love for those who cannot) we are mini-heroes you know!

That’s a good point about people using the “you don’t seem that autistic” to absolve themselves from any responsibility for accommodating or acknowledging our struggles. I’m in the process of writing a post about disclosure and the issues it raises. It seems nearly impossible to disclose and then not have the relationship change, if only in subtle ways.

And applause all around! We’ve earned it. 🙂

“You’re so smart! How can you be so stupid?” is something I heard so many times growing up.

It’s so sad that people feel the need to be that blunt, especially to a child. 😦

aww, this makes me sad to read how hard others and ultimately you are on yourself for the social skills stuff. It breaks my heart to see how hard my son tries sometimes to play with other kids and to have him ask me what he did wrong when he is rebuffed by them. It takes a whole lot of self control on my part not to say to him what I really feel which is – sometimes people are just @ssholes. So I am going to say it to you now instead. If someone stopped inviting you over because you broke a wine glass and didn’t offer to replace it then they are an @sshole. seriously people irk me, there are more important things in the world for them to focus on. social rules and norms are great in as far as they help us all live together harmoniously but to push them to the point that we use them to judge and humiliate another person instead of looking at what unique and wonderful things they have to offer the world then we have lost the point. {steps off soap box now….}

I think the “hard on ourselves” often grows out of others being hard on us (intentionally or not), though not always. There’s also the black and white thinking aspect of AS which leads to sometimes unhealthy levels of perfectionism. The thing about the glass–I have no idea. There could have been any number of reasons for the sudden freeze out, including the other person being an asshole.

Thank you for the dose of perspective. The thing about growing up with zero clue about social interaction is that it breeds deep self-doubt. Whereas someone more socially adept might blow off a slight as being the other person’s problem, I think we tend to automatically look inwardly for an answer. Often I’ll come around to realizing that the other person is in the wrong or not the kind of person I want to associate with, but it takes a bit of mental gymnastics and looking at all of the angles first to get there.

so I regretted writing this not long after I hit post because I realize it comes from a place of privilege to be able to say screw them it’s their problem when indeed social queues are not something I have never had any real struggle with and I did not mean to be diminishing as I feel this came off.

It just comes from an area of deep pain for me to understand these rules and want to so deeply to teach them to my son and to in turn have no idea how to break them down into rules that make sense without a hundred caveats to every rule.

~ It’s very important for you to say please and thank you ~ but it’s not ok for you to point out to other people when they do not say it ~ but it’s ok for me to point it out to you because it’s part of my job as your parent ~ but yes that other person did point it out to you and they aren’t your parent ~ but we aren’t going to point that out because that is also not ok ~

it gets crazy trying to break it down into easy to follow rules and then I feel like a failure that I can’t help him.

Hey, you’re fine. I did read it as coming from a mother’s pain and frustration, so no worries. Also, I’m super literal and so answered in a very literal way, not in a way that was meant to imply anything. 🙂

Your perfect example is perfect. There are so many exceptions to so many rules and really all you can do is keep explaining. All of them, the rules and the exceptions and the exceptions to the exceptions. He’s absorbing and remembering and you’re giving him the tools he needs to build his database of rules. It’s so much easier (and I think safer?) to get stuff explained than to have to guess at it. Don’t feel like a failure! This is hard stuff. I’m still learning it at 43.

This post is spot on and brilliantly written, but I think you missed something common that’s really important for the adults around doubly exceptional to be aware of.

I think kids labelled gifted who struggle to succeed socially tend to build their self esteem on the idea that they’re the smartest and best, constantly praised by teachers, and so ‘better’ than the kids who won’t be friends with them and maybe even tease or bully them.

This sort of attitude can work in the short term but almost inevitably results in a moment at some point later in academic life where they stop being the best, or find something they can’t do, and so have an identity or self esteem crisis. Maybe all the cruel things other kids said to them start being taken as true because the only self defense they’d built against this was predicated upon the continued praise of teachers and other adults, or the validation of good grades or awards.

This is something that I really hope the system does better with than they did when I was a kid; teaching kids they have value that isn’t just associated with success, that they’re liked and loved even if they don’t do well. When you’re used to working hard and getting the best marks it can be shocking and disturbing to work hard and still not excel (and black and white thinking can mean you think of anything but the top grade is a failure).

I wasn’t given special advanced subject workbooks (unlike my brother) because there was always something that I was ‘inexplicably’ bad at like spelling or times tables, but I was on the advanced reading books, given art and computer programming projects away from other kids, and I was always placed on the ‘top table’ in class and got As in most subjects. In adulthood I know that I have ‘genius level’ verbal reasoning skills and am either average or extremely bad everything else, which means that I solved all my nonverbal academic work by brute force verbal reasoning. In childhood I had no idea about that, just knew that I’d be utterly brilliant at some subject up to a point and then suddenly wouldn’t be able to do it at all, with no understanding as to why.

For maths this point was, unfortunately, halfway through A-Levels (16/17 years old) where it was one of only 3 subjects I was studying and incredibly important to do well in. I went from getting As in the first 2 modules to Es in mocks for the rest. Even with a huge amount of specialist private tuition, I only got a D overall (turns out I’m below average nonverbal reasoning and I’m in the bottom 1% for mental arithmetic, so it’s impressive that I was managing to get As in maths until 16 really!). The effect on my self esteem was crushing, but luckily I eventually got an unconditional university offer after clearly being brilliantly passionate about programming at interview.

So, yes, it’s incredibly important to teach kids that their value doesn’t come solely from success, that being the best doesn’t matter, being happy and doing what you love is more important. It’s also important not to ignore obvious learning style, academic or social oddities just because the child is getting good grades right now – if the kid has SpLDs or an ASC then at some point their challenges are going to cause serious problems and their self esteem is much more likely to be more fragile than typical kids’.

Good point. I’m glad you expanded on this. I think I intended to start down that path when I wrote that there’s no gifted class in aduthood and no one really cares how good you were at memorizing the week’s spelling words. Adult life is complex and intelligence doesn’t always count for much, or as much as you’d think it should, especially for those of us who don’t present in a typical way.

What you say about being brilliant up to a point and then not being able to continue resonates with me. I skated through math without making much effort until I hit Algebra 1 in high school and couldn’t make heads or tails of it. I went through life after that assuming I was “bad at math” until recently. When I returned to college, I had to take calculus as an econ prereq. I discovered that I’m not bad at math if someone teaches it in a way that makes sense to me. Fortunately I had a patient calculus teacher who was willing to explain things a half dozen different ways until we all got it (it was a very small class) and who didn’t care how we got to answer as long as it made sense to us and we could do it consistently.

Your last paragraph is so important. I wish more people in education were aware of this. The ability to get good grades doesn’t mean that everything is find and dandy in a kid’s life or even in their academic life. Do you know of any studies about ASC and self-esteem? I know that mine isn’t the best and when I was younger it was quite awful. Now I’m curious whether this has been formally studied in any way.

**nods** yes I took that you were going in that direction when making comparisons to adult life, but I think our status as gifted is often shattered well before we reach adulthood, especially as academically successful students are generally pushed to do their very best and so rushed towards their limits. If anything we’re more likely to go into adult life not thinking we’re brilliant because we could do complex algebra and spelling bees, but already feeling like we’ve failed to ‘reach our potential’ or that we’re ‘stupid’ for only being above average, not the greatest possible academic elite.

Depending on our abilities, our choices and luck, this can happen anywhere from primary school up to during the process of gaining a PhD. At some point we hit our academic limits or we raise to a level where our giftedness isn’t anything special any more and at this point we need to have strong foundations of self esteem and a social safety net to prevent this from being traumatic.

I wonder if this is perhaps less of an issue if you’ve always been part of an organised gifted or honours programme. At my school you weren’t taken out of class and mixed with other kids of similar ability, you were simply the smart one being given special treatment in a mixed classroom. Perhaps having others who are also considered academically special with you at least produces some degree of camaraderie and realisation that others are better at you in some academic areas? I’m not sure though because I’ve read others expressing similar sentiments, and also that being part of those programmes produced more social stigma and so more of a defensive ‘us and them’, ‘they’re all stupid anyway’ mentality.

As for research into ASCs and self-esteem, if anything the research is on the endemic levels of poor mental health which can be tied with feeling socially and/or academically deficient. Be it depression, anxiety, self harm, eating disorders, OCD etc, all of which can be traced to having very low self-esteem and very little feeling of control in ones life. The UK National Autistic Society has a good overview of this:

http://www.autism.org.uk/working-with/health/mental-health-and-asperger-syndrome.aspx

I think I was a bit of an anomaly in this regard because I went from the gifted class in 6th grade to a parochial middle school that randomly placed me in classes that were too easy. It was a shock to no longer be “special” and my response to that was acting out in lots of inappropriate ways because I was bored senseless academically.

When I landed in the principal’s office in October, threatened with expulsion for fighting/bullying on the school bus, I told her I was bored. She told me if I got all A’s she’d move me to more challenging classes. I got straight A’s the next quarter, took my report card to her office and she told me she couldn’t really move to different classes because it would be too disruptive. That pissed me off to the point that I started doing the bare minimum to get by in class, which required next to no effort.

High school was much the same. I wasn’t really challenged intellectually past 6th grade and by the time I hit the Algebra class that made me think I was bad at math, I had such a crappy attitude about school and about life in general, that I found it easy to blame the teacher for my C. Then again, that may be a textbook definition of poor self-esteem right there. 😉

I’ve bookmarked the link to the article about mental health and AS. I’ve struggled with depression at times and I think I have low self-esteem tied more to social/behavioral experiences (as we’ve discussed rather at length I guess) so I’m interested in reading more.

Thank you! You’ve put into words something I’ve always felt. I was only diagnosed recently, and have gone through life as puzzled as anyone around me how someone could be so smart at difficult intellectual things and so dumb at easy daily tings everyone can do. It’s good to have an explanation, and find out that I’m not the only one like this.

I’m so glad you found it helpful! It was always puzzling to me too until I got diagnosed and came across the doubly exceptional label.

I think you have explained me & have explained to me. Very much in line with my own experience except that I am even older & am male. THX just because we grok Einstein doesn’t mean we grok party manners. Stopped going anywhere years ago because everything I do is wrong I get no explanation only violence or shunning. Neurotypicals very filled with intolerance and wrong expectations. Lots of work I could do well but employers explicitly advertise “must be team player” excluding all aspires. Why the hate? Just how they are.

The “team player” phrase in so many job descriptions is a killer. As are all references to strong people skills or communication skills. Some jobs of course require people skills or the ability to be a team player, but as you say many could be done just as well independently.

klaatu, I totally agree! I’m also in a business profession where social skills are strongly emphasized (how I chose this field, I have no idea). Many in my profession emphasize social skills and building relationships. Business is so fraught with this jargon. You have to have “vision,” be a “leader,” be “extroverted,” be a “team player,” and to “connect.” Yet not every leader in the world is boisterous or extroverted, and even in business, you CAN balance independent work with team work. I’m slowly learning to fight for my own “introvertedness” and “awkwardness” in a way that other people can at least try to understand.

So much of this (comments as well) sound like my now 11 year old son who was readingThe Marvel Encyclopedia cover to cover at age 2, relishing every word and image. He has always been acutely aware that he is different. He tells me quite regularly that he “fakes it” all day, every day at school in order to have “friends”. He says that knows they aren’t truly his friends because they don’t know him at all…They know the facade. He executive functioning skills a nightmare…He lives in a constant state of disappointing everyone…Never remembering the book, the assignment…Not giving a rat’s ass about spelling and the “simple” stuff that he is “beyond”…but looking at a page of math problems and being so overwhelmed he cannot break it down into steps/parts…stimming constantly through homework…and self-depricating constantly. And I seem to be the only person who thinks he’s Aspie…Of course, not one person believed that his 4 year old brother was Autistic at 18 months when I decided it was so…And it is SO very so…It was his diagnosis that led me to truly reflect on my precious oldest son who I always described as “too good for the world at large”. And he IS too good for the world at large. Thanks for the post and to all those who commented after.

Your description of your son is heartbreaking because I can relate to so much of what you describe. I’m not sure whether having the label would be helpful or not, though I think your recognition of his differences is crucial, especially the fact that you know it’s his executive function and not some sort of willful negligence that’s causing him difficulties.

Faking it, sadly, seems to be how many of us got through school. There aren’t a lot of good options. If it helps at all, I (and it seems lots of others) felt much less out of place in high school and many autistic folks describe college as heaven.

I can relate to this. I was always labelled “shy” at school and preferred to sit and read rather than join in play with the other children. I was in the top sets for maths and physics, and was entered in national competitions by my teachers in which I won gold awards (placed in the top 10 in the country in my age-group for physics). But I only ever had a few (3-4) friends and didn’t ever feel comfortable with most of the other pupils. I went on to Cambridge University to study Natural Sciences (Physics) but failed my second year and dropped out – I never managed the transition from the structured environment of school, and with hindsight it was a combination of poor executive functioning and a lack of social skills that left me feeling out of my depth. I feel now that if I had been aware of AS at the time (early 90’s), and there had been the appropriate recognition and support available, I would have coped a whole lot better.

I agree with the point raised by Quarries and Corridors about one’s self esteem being built on a reputation for being the best in a particular field and needing the reinforcement of praise: I still have trouble accepting it when I fail to meet my own expectations and I find it acutely embarrassing to admit to such failure because it is so tightly coupled to my self-esteem.

You make a great point about the need for supports in transitioning from high school to college and then on to adult life. Each step is progressively more demanding and unstructured. I went straight from high school to marriage and then motherhood soon after, which was a huge shock. I was lucky to have my husband there to shoulder a lot of the burden (he still does, really). I’m not sure where I would have ended up without him. I doubt I would have survived college.

Having high expectations and some degree of perfectionism seems to come with the AS territory. I’ve been writing about this a bit for a later part in this series–about letting go of my more unreasonable expectations of myself and making an effort to be kind to myself, which is a foreign concept for me.

For me, “if only I tried a little harder” was also “why didn’t I think of that earlier?” It explains a lot about many of my meltdowns and why moving to a new school that emphasized social ability above all else was extremely frustrating. This school, in particular, had many unspoken social rules that I never learned and therefore had a hard time picking up on. Everyone here did expect you to swim in the deep end of the pool, without question. And there were only 5 people in advanced math. It was a stark contrast to the school I was in before that. The other school focused on academics and overall was very diverse: you had just as many “geeks” as you did the “jocks” so it wasn’t hard to find your niche at all. There was as much a focus on academics as there was on social skill, but if you were lacking somewhere it didn’t matter. Because there were other people who were awkward in varying degrees too. I think I was equally awkward in both settings, but I didn’t feel much pressure in one versus the other.

I guess what I am trying to say is, an ideal culture for me should celebrate diversity: in nationality, race, sexuality, and even academic and social skill, and to do so and help anyone who needs it without passing judgment. I felt more accepted in one setting despite being awkward and still found my niche even though I didn’t have many friends. Yet the other setting I couldn’t do the same because people were less understanding.

Yep, I know exactly what you mean. In fact, my daughter when to two high schools–our regular public high school in the morning and a performing arts high school in the afternoon. The arts school was exactly like you describe, very accepting of differences, and she thrived there. Her regular high school was a much less diverse environment and she came to hate it because she was faced with such a start comparison every day.

I still have the “why didn’t I think of that earlier?” problem. Quite often, I realize what I really wanted to say in a conversation hours after it’s over!

The school you moved to sounds rough for someone with social communication difficulties. At least in an environment with an academic emphasis, we can fall back on being good at a particular subject or at least bonding with others who share common academic interests.

musingsofanaspie, I agree about being in an environment with an academic emphasis. I’ve looked back at my life so far and found that I’ve really thrived in settings that were both highly structured and geared toward different strengths, not just social politics.

musingsofanaspie, I can also relate to your broken glass example. I went through a similar experience. In Eastern culture, it is customary for people sitting at a table to wait to eat until the elders have begun to eat. I had spent 2 years as a young child in such a culture, but this was not something I noticed. Years later, my whole family and I went back to visit relatives. My younger sibling, who was too young to remember growing up in this culture, identified this custom very quickly, and reacted accordingly. He even warned me away from the food because he noticed that an elder had not eaten yet. It led me to believe that many people are instinctively aware of these little nuances and minor variations in a group or even a culture, even if there are language barriers.

In fact, they can know it so well that it becomes hard to teach someone who doesn’t how to identify them consistently, so I could see why some people will have a default response of, “Try harder!” But I think for anyone with limited social abilities, being social in itself becomes a deliberate, intentional activity. Like telling yourself every step you need to take to ride a bike.

The bike analogy is great! It’s like socializing never quite becomes second-nature in the way that riding a bike quickly does and every time we “get on our bikes” we have to pay attention to the mechanics of it instead of enjoying the ride.

I can relate to this entire post. ALL OF IT.

I was expecting you might say that. 🙂

I went through around seventeen different schools in an attempt to ‘fit-in’, thinking that it’d work eventually. It never did. Sometimes I wonder if I would’ve been diagnosed, had I stayed in one school long enough for the teachers to notice a problem. Some did, some wondered why I had such a difficult time relating to and conversing with my peers, but I think that many of them attributed it to my intellectual capacities. See, I could hold a perfectly academic conversation with my teachers and other adults, wowing them with insights that they wouldn’t expect from a little girl… but when it came to the other kids, I just seemed bossy and clumsy and they probably considered me a teacher’s pet or a know-it-all – I know that I came off that way. Still do, in fact. It’s much easier to just spout off information than it is to try to relate to things that I really don’t understand- like boys and clothes and music. I can force myself to a certain extent, but I have no tolerance whatsoever for those things. Sadly.

But then again, maybe adults just have a better tolerance for quirks like mine. I know that it won’t always work- I’ve been noticing how offended some people get when I correct them now that I am older. Therefore, I have concluded that that particular coping mechanism won’t last me much longer… what do?

I’m starting to prefer children, now. xD They are truthful and honest and very, very curious. It is beautiful.

I didn’t really show any obvious schoolwork-related deficits (other than trouble with multiplication tables and reading clocks and anything mathematical xD) until around middle school, when our handwriting was supposed to be more acceptable along with our writing skills. See, I may be well-spoken while typing, but I completely lose that ability when forced to handwrite. I mean, I still DO have the same words, but handwriting causes me so much hardship that I just… can’t do it. It takes too much physical+mental effort for me to write out the words and make them coherent all at once. It was a noticeable issue in school, but now that I’m back in homeschool, it’s much easier because I can type!

And then there are the math issues. @_@ I make really simple mistakes with things like addition/subtraction/multiplication/etc., I can’t grasp the concepts too well unless they use more complex explanations, and the handwriting is, once again, painful.

Ah, learning issues. >.<

And yet I was reading Stephen King at the age of nine and I have the reading level of a high-level executive. /sigh

Oooh, look at me rambling. I'll stop now. XD

I know exactly what you mean about relating to people of different ages than yourself. I was more comfortable with adults as a kid and these days I’d much rather amuse the kids at a social gathering than try to converse with adults. Also, as a teenager, people always thought/said I seemed older than I was and as an adult people routinely tell me that I’m “young for my age”.

People really don’t like being corrected, even when it seems like correcting them would get things done faster or save them some hassle.

Handwriting is a problem for many people on the spectrum, thought it seems like it’s particularly bad for you. I have a problem with getting all of the letters in the right order when I hand write things. Like I’ll write the first few letters of the word, skip one or two, finish the word, then go back and cram in the missing letters where they belong. My handwriting is also mostly illegible to other people.

Do you prefer homeschooling overall? It sounds like it allows you to go at your own pace and get the sort of supports/accomodations you need to learn in the best way for you.

I loved Stephen King as a kid, too! That’s kind of warped, isn’t it? 🙂

Wonderful post. I was also a doubly exceptional child before that term existed (I was 18 when the Aspie diagnosis was added to the DSM), and from grade 4 to 6 I spent one day a week in a gifted class. My parents were given the option for me to skip a grade, but given my mom’s difficulties with that, and my difficulties with social interactions, it was decided that I wouldn’t.

I then got into a high school that was known for its academics, which meant I encountered the “other people are as smart as you” kind of early on. (Well, I encountered it when I was seven or eight and taught my two or three year old brother basic arithmetic, but anyway….) Unfortunately, one thing elementary school *hadn’t* taught me – because of that “gifted” label – was how to do homework, and not let the perfectionistic attitude affect it. Boy, did I ever suffer from that in high school. My mom remembers (though I don’t – more of those repressed memories) finding a late physics or chemistry project in my room, completed, and asking why I hadn’t submitted it, and me telling her that it wasn’t perfect yet.

The homework stuff (and the fact that having taken advanced classes, and in a different province that went one grade higher than Newfoundland, where I came for university, meant that I took no courses directly towards my potential degree in first term) screwed me for university.

I identify with a lot of the commenters. “Shy”, “if only you’d tried harder”, “*why* can’t you try harder”, “why didn’t I think of that”, “why couldn’t I think of that quicker” (the latter around my middle sister and our verbal spars most often)…. I heard all of those. A lot from myself, after some came from other people. And yes, *seriously* beats down on the self-esteem.

I always seem to have long answers to your posts, I notice. Anyway, there’s my $0.20 (inflation, you know… ;)).

🙂 tagAught

I think skipping a grade could be disastrous for kids on the spectrum. I was already so far behind socially that skipping probably would have left me completely bewildered. Plus I would have lost the few friends I had.

Perfectionism! I have it. Apparently perfectionism in aspies is related to black and white thinking. A thing is either done perfectly or it’s a disaster and there’s no in between for us. I have similar issues with completing things. Like, if I don’t think I can finish it in the (often made up by me) allotted time period, I won’t even start because leaving something undone is so hard.

I love your long comments. I’m thinking that when we answer the survey questions, we’re all going to break the comment box. 🙂

I’m another doubly exceptional student (diagnosed ADD but I think ASD would be more accurate), I think a generation younger than you. I wasn’t identified as having anything “wrong” with me until high school and at that point it didn’t really matter anymore. The “supports” that were suggested/used did more harm than good: take away her book until she’s done with her work. The allowances that teachers made before that were actually way more helpful: leaving math assignments in the classroom so I couldn’t take them home and lose them, being allowed to do history research on my own and write an essay instead of having to try and read the textbook and do the worksheets, writing my own English essay prompts. It was definitely helpful that my highschool was small enough that teachers got to know each student individually, and students keep in contact with teachers for years after graduating.

Throughout elementary school, I didn’t mind the busywork as it kept me entertained just enough. And I didn’t have any serious difficulties (aside from the homework issue) until high school–where I couldn’t absorb anything from most of the grade-level textbooks but had no trouble with college-level or honors textbooks. I guess it makes some sense, considering I don’t remember not being able to read.

I loved my small schools and made some friends and am still in touch with most of them from high school. But in college… it just doesn’t work. I have a friend who thinks it’s just maturation and it’ll happen eventually if I just interact–even though he accepts the fact that I have no common sense. And I had a teacher say I was the “stupidest smart person” he’s ever known. I don’t know where I’m going with this anymore, so I’ll just stop.

I’ve heard quite a few people say that college was a big stumbling block. Whether you are ADD or ASD or both, the impact of executive function issues alone is enough to make transitioning to demanding, unstructured atmosphere of college a huge challenge. I spent years thinking I would eventually “grow up” or grow out of my problems with day to day living and social interaction but it never happened. I’ve gotten better at being organized, coping, etc, but there’s a lot of stuff that I think is with us for the duration.

Most colleges have disability resource centers, though with varying degrees of helpfulness. Maybe something to consider if there are specific supports or accommodations that you think would be helpful for you?

Yeah… executive function issues plus an apparently unusual degree of pickiness is really problematic. I can’t eat most of the cafeteria food. So I’m really glad I can cook. But that reduces the energy I have for schoolwork and socialisation.

I’ve thought of a few accomodations that would help: non-shared bedroom, reduction or elimination of the requirement to speak during class, possible reduction/elimination/huge change (ideally independent study) of the foreign language requirement. I’m kind of hesitant to go to the disability resource center, though, without a definite diagnosis.

I would imagine the college would want to see a formal diagnosis, yeah. 😦 I was wondering if perhaps your ADD diagnosis could be used as a substitute way of getting accommodations but it sounds like you need mostly ASD-specific accommodations.

I somehow got through most of my college courses without ever speaking in some classes. Others were harder because there were presentations or mandatory discussion and I suck at both. Presentations are like organized torture.

No lie: I lost 60lbs in my first year because residence food was so bad and cooking my own would’ve meant dealing with people (I don’t do social when hungry), so I pretty much lived on the salad bar.

It was 60lbs I could easily afford to lose (my parents cook with truck stop portions and calorie content and would pull the whole “You don’t leave until you clean your plate” thing, so I was overweight), but still. Not a good way to lose it.

To cinvhetin (and all with similar doubts/problems): I don’t know which university you’re at but just go and tell your tale at disability services. I never did (I did circle regularly the offices without ever mustering the courage to walk in, I was just too shy and ashamed of my apparent disability) and came away with no degree. I made sure my children got there and both received help that definitely helped them to get a degree, helped them to not drop out like I did without that bit of help that might have allowed me to cross the line. Since then, I have learned that others with similar problems (executive functioning in my case) have made it to get their degree due to a professor that somehow got them and got them to make that final effort. And I listen to their stories wishing that I’d met a professor like that… well, I’m jealous, amn’t I?

My comment may come late for you but I very much hope that it stops someone from dropping out like I did without the university ever knowing why I left in the early eighties without a degree.

That’s what I kept assuming too, even though everything I experienced contradicted it. One that I would cross the line and “get it”; pass into the world where I would be a real adult who be in a way so I would fit in, people would consider me part of the social scene et.c.

I am not gifted, just normal and have not been in a gifted programme or something like that. But I was a faster learner than most of my class mates and considered smart and “extra mature”, being intellectually inclined and relating to grown-up concepts from an early age so I can relate to the principles of what you describe. I recognise the assumptions that since XYZ was so easy for me and I “had so many talents” then I would do well and people scratching their heads when reality proved otherwise and I failed all the bare minimum expectations people have to anyone (make friends, go through high school, manage life practically, perform entry jobs satisfactorily and found a career direction). They didn’t realise while it certainly helps to have a good head, the social barrier was so high that I couldn’t even get to use and build on my strengths, I couldn’t get to the starting points. E.g. if you want to go to university then you have to go through high school first (impossible – at the time where it was normal to do it ~ youth years) and if you want to get a career, then you have to be able to do well in some “easy” job first. If you can’t get through the “easy” stuff then it doesn’t help much to have an advantage with more complex stuff. Eventually, in a mature age I did manage to go through the education system and have a master degree, but still have the same problem with establishing a career and passing the basic expectations in order to get to use my qualifications.

Thanks for a great post:-) I’m not sure why I initially overlooked it.

I’m curious how long you kept thinking the “growing up” would happen? I held that notion well into my late 30s, which is bizarre when I think back on it.

I couldn’t get to the starting points.